The optimist’s paradox

Monday, October 27th, 2008

Insolvency shadows media companies

The trading trajectory of media company shares over the last month bears an uncanny resemblance to trading in the shares of companies like Bear Stearns and AIG in the weeks leading up to their bankruptcies. Look at the chart here and see how WPO, NYT and CBS have plunged much more dramatically than the overall market.

Media companies face a number of what might be politely called “challenges.” (Or, more bluntly, razor-edged threats resting on their jugular veins.) In a downturn, corporations slash ad spending since this is often their biggest and easiest discretionary spending line item; advertising makes an easy, fat and juicy saving. The advertising contraction’s impact is exacerbated in this downturn, because cash flows are frozen. There’s no doubt that the normal industry AR age of 90 days will stretch out to… 120 days? 180 days? In a normal environment, media companies could borrow to cover the cash flow shortfall, but this is no normal environment. Here’s a graph of the way WPO has traded this week:

Huffington post-mortem

With all this in mind, today’s NYTimes credulous piece about the Huffington Post and its young sibling The Daily Beast was particularly amusing. The journalist takes at face-value the assertion that things are swell.

In the short term, The Huffington Post could make Ms. Huffington even richer than she already is; if the site were to be sold, the value that is often mentioned by people with knowledge of the site’s finances is $200 million. A person briefed on the site’s finances says it is not for sale, but that another financing round of more than $5 million could be closed by the end of the year. Over the last three years the site has raised $11 million — underscoring the site’s ability to attract traffic on a shoestring budget.

$11 million is a shoestring budget?

Here’s that verbiage really means: “has raised $11 million” means Huffpo has lost $11 million since it was founded. And now “raising more than $5 million” means the site expects to lose another $5 million in the coming year or so. That’s success on a shoe-string budget?

In an environment when potential acquirers and competitors are all nearly insolvent themselves (see paragraph one), only the looniest of investors will fund a money-losing Huffington Post for anything less than an punative share of the company.

The optimist’s paradox

Ms. Huffington faces a horrific dilemma that might be called the optimist’s paradox. Huffpo is most likely nearly out of money (hence the need to raise $5 million in coming weeks.) And while a prudent manager who sees her cash running low would trim expenses, Huffington can’t afford the psychological horror of cutting her payroll because this would clearly contradict what she’s busy telling potential investors… that all is well and she’s incredibly optimistic about next year.

So, instead, Huffington has to speed ahead towards the abyss hoping some white knight steps in to build a bridge to profitablity. She has to hold on to her mask of shocking optimism right up to the moment when the last potential sugar daddy steps away from the bargaining table. (And smart potential buyers will, knowing this is a buyer’s market, be tempted to string her along towards the moment of insolvency to increase their negotiating leverage.) If the knight doesn’t arrive in time, Huffington won’t have enough cash to fund even a skeleton operation.

The un-layoff list

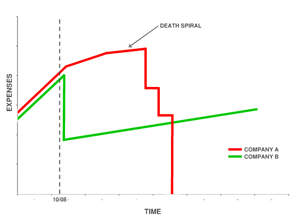

Which brings us to the unlayoff list. You’ll no doubt recall the TechCrunch layoff tracker. Companies tracked there have tallied 22k layoff in the last month. Yet, weirdly, those companies are some of the healthiest of the money losing startups. For example, Adbrite cut 40% of its staff… but is now profitable. In contrast, unprofitable startups that are not laying people off are either a) so far from being profitable that they can’t conceive of ways to cut enough costs to get to profitablity or b) trapped in the optimist’s paradox and can’t cut lest they alienate potential buyers or c) both. (Thanks to Sequoia Capital, which has seen plenty entrepreneurs go down this path, here’s a graph.)